X-Men: X-Cutioner’s Song was a crossover comic book event of the early 90’s, running from November 1992 through February 1993. While it was a crossover event, all of the involved titles were X-Men related: Uncanny X-Men, X-Men, X-Factor, and X-Force. It’s fitting that the story keeps the focus intimate, as the catalyst for the event is the attempted assassination of the mutant patriarch Charles Xavier, aka. Professor X.

I’ll admit, X-Men events can get complicated. I’ll sum it up as follows: Professor X is shot by a man who appears to be Nathan Dayspring, aka. Cable, the time-travelling mutant soldier. While Professor X is left comatose and infected with the futuristic techno-organic virus, the X-Men and the government-affiliated X-Factor attempt to track down Cable, starting with his former team X-Force. And while this is happening, Cyclops and Jean Grey are kidnapped by the mysterious villain known as Stryfe.

That’s the broad strokes premise: Why did Cable try to kill Professor X, and what does Stryfe want? And within this, we have multiple factions at work: the enigmatic Mister Sinister is scheming in the background, Apocalypse is woken up from his hibernation by his followers because of Sinister’s schemes, and the anarchist group known as the Mutant Liberation Front is being used by Stryfe for whatever his violent goals are.

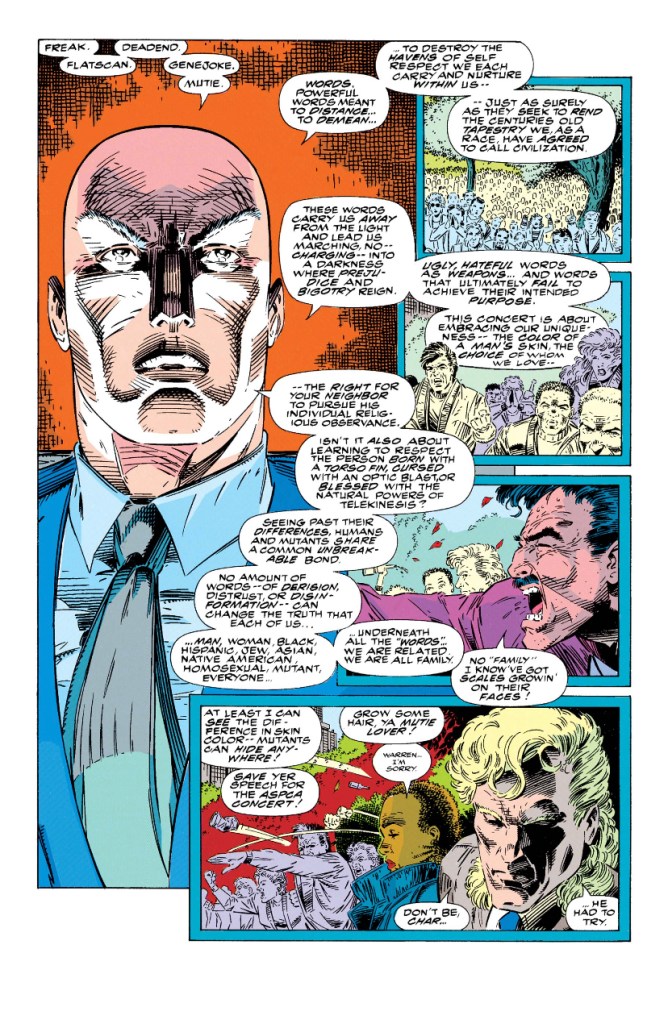

While these events may all seem separate and convoluted, there is a theme that ties them all together: legacy. Let’s start with Professor X and his legacy, as this is also the beginning of the X-Cutioner’s Song event. Charles Xavier’s dream is at the core of all X-Men comics: the idea that peaceful co-existence between humans and mutants will one day be a reality. That mutants will no longer have to live in fear of prejudice or violence, and that humans will not judge them purely out of fear.

Professor X formed the X-Men to fight for this dream. To fight both humans who target mutants, and mutants who target humans, as both are obstacles to the goal of co-existence. The X-Men and Professor X’s students are sometimes referred to as “Xavier’s children”, and Apocalypse’s minions even refer to them in this event as “Children of the X”. There is no doubt that Professor X serves as a patriarch, a father-figure and mentor to all of his mutant students and former students.

The threat of Professor X’s death has the same effect on the X-Men as children facing the fact that they might lose their father. They gather at the hospital, angry and restless. The reality is that they don’t know how to cure their father figure of his ailment, and instead they seek to channel their anger and restlessness into action by tracking down Cable. The art style of the X-Factor #84 in particular hammers home the grim reality that they X-Men are facing: the harsh lines, the detail in characters’ faces, and use of shadows forming a bleak hospital setting.

Acknowledging the pain and helplessness that Xavier’s children are feeling leads us into how they feel about each other. In essence, the core X-Men team consisting of classic characters like Storm, Wolverine, Colossus, Iceman, Beast, and Angel (Archangel, at the time) is the closest model of what Professor X wanted the X-Men to be. They’re willing to work with the government, but not be subservient to it. They’re willing to take violent action when necessary, but only in dire times or self-defense. The X-Men are mutants who act according to an optimistic philosophy that chooses a path of nonviolence when possible.

Let’s compare them to X-Factor: a group that works closely with the government, consisting of characters like Havoc, Polaris, Multiple Man, and also the younger Wolfsbane. This is Xavier’s dream taking a different path, one that says maybe working within the system is a better path to forming a bridge between humans and mutants. It should be noted that Xavier’s original X-Men did start X-Factor before returning to the core team, showing a shift in the characters’ personal philosophies.

And finally, we get to X-Force, who were formerly known as the New Mutants. This team consist of the younger, more rebellious mutants like Cannonball, Sunspot, Boom-Boom, and Rictor. And as Cable led them for a time, this is the more militaristic group that’s prone to violence when their leader, Cannonball, isn’t reigning them in. This is essentially a generational clash: the traditional Baby Boomer-era X-Men and X-Factor vs. the rebellious Generation X-era New Mutants/X-Force.

So we see that Xavier’s dream has gone through struggles and evolved to face them: Some mutants keep closer to his philosophy while others are looking for a different path, but they all want the same conclusion. These characters have all worked together, in one way or another, for years. Some served on the same teams, some fought the same enemies, and some are genuine friends. We essentially have a family of mutants and outcasts, bonded together by their mentor and their struggles. And just like any real family, they disagree, but they still support each other, despite their personal philosophical differences.

Xavier’s legacy is the X-Men and their splinter groups, and their feuding represents the clash of ideas that’s always at the core of X-Men stories: is Xavier’s dream plausible in a violent, fearful, and unjust world? Can hope and optimism survive reality?

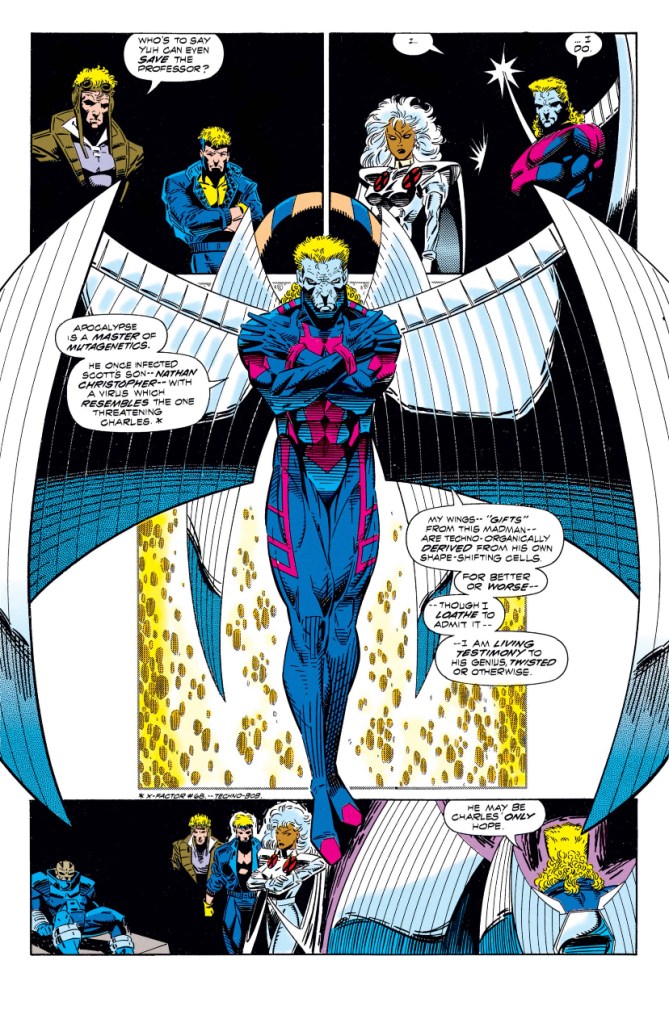

The next example of the legacy theme in X-Cutioner’s Song is the antagonistic relationship between Apocalypse and Archangel. Apocalypse, the ancient Egyptian mutant who often plays the villain, has a singular philosophy: survival of the fittest. Ironically, he’s caught completely off guard in this story. He’s woken up from his regenerative slumber with little explanation and is ambushed by both the X-Men and Stryfe throughout the story. X-Cutioner’s Song is one of the few times that we don’t see Apocalypse orchestrating events, as all he knows is that someone has been disguising themselves as him for their own agenda.

Angel was one of the founding members of the X-Men, or the Original 5, as I like to call them (occasionally, the OG’s). Angel, however, suffered from having the relatively “lame” power of flight via feathery wings. While that was fun in the 60’s, many super heroes just fly as a nice bonus to their other exceptional powers, so Angel was in the unfortunate position of being too weak.

This led to the creation of Archangel: Angel’s wings were brutally taken from him by villains, and in his depression, he agreed to let the Apocalypse replace them through a painful surgery. He got an upgrade in the form of metallic, razor sharp wings that could be thrown like knives, and also had the side effect of blue skin. I think Archangel is extremely cool, with the whole visual aesthetic completing his newer “dark angel” persona. And my favorite color being blue helps, of course.

However, with this power and visual upgrade came a personality shift: Archangel became a brooding figure, often with violent tendencies. And of course, he blamed Apocalypse (who did in fact try to brainwash him) for his problems. In X-Cutioner’s Song, Archangel both serves as the primary character who doesn’t trust Apocalypse and wants to kill him, while also being the only one to come to his defense when he’s helping cure Professor X.

This inner conflict is referenced in their conversations. Apocalypse directly refers to Archangel as “son”, which the latter shrugs off with disdain. Apocalypse is definitely taunting him in a sense, and the most effective taunts have truth in them. Apocalypse is referring to the legacy he has Archangel to carry: Archangel was one of his four Horsemen, taking the title of Death. He served Apocalypse once, and now, he serves as a walking testament to the villain’s scientific genius and violent philosophy.

At one point in the story, Archangel accidentally kills a villain who was charging at his back. He turns too quickly, slicing the man’s head off with his metallic wings. While Archangel clearly is surprised, he shrugs it off and focuses on his goal. This is Apocalypse’s hardened philosophy at work: Archangel wastes few words or thoughts punishing himself for the killing, though Iceman does call out his friend, letting him know that he won’t let him off so easily.

In Archangel and Apocalypse, we see a toxic patriarchal relationship. Apocalypse sees himself in Archangel and is proud, while Archangel is disgusted by the resemblance. Archangel is in constant rebellion of the legacy that Apocalypse is trying to leave him, though that’s difficult since his legacy is woven into Archangel’s very body. The metallic wings, the blue skin, the menacing persona: all of it is a threat to Archangel’s very sense of self.

Archangel defending Apocalypse as he cures Professor X is symbolic: he allows his original father figure to be healed by his new one. In fact, he’s the only one who knows that Apocalypse will follow through on his word. That implies a sense of trust between the two of them that no one else shares with the villain, and that in itself is a testament to how deep Archangel’s struggle goes.

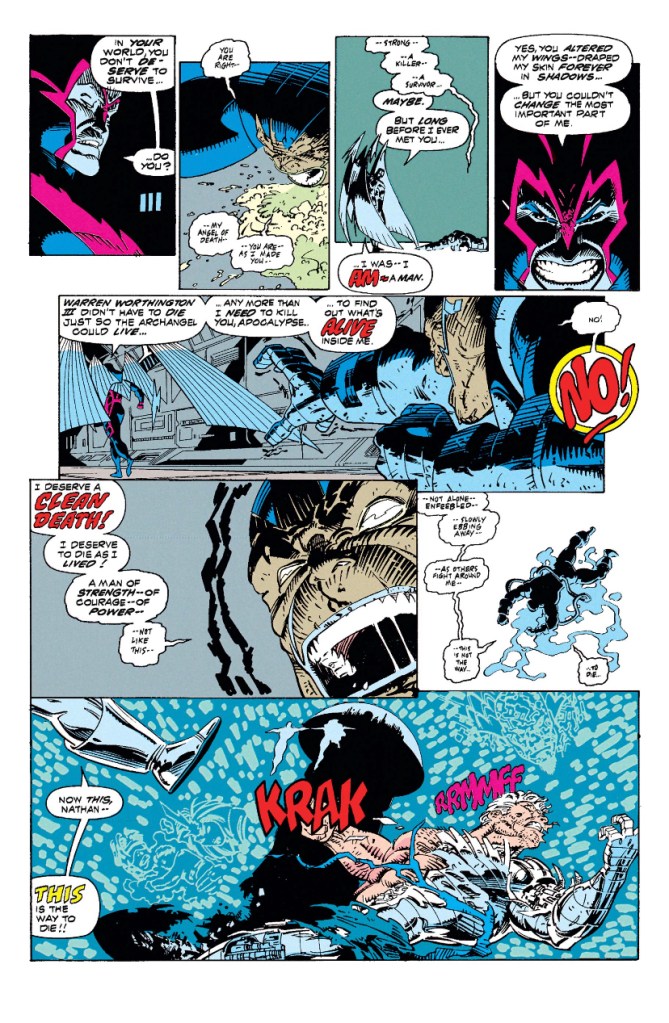

In the end, when presented with the opportunity to kill Apocalypse, Archangel denies the villain the satisfaction of knowing that he’s truly made Archangel into his violent heir. He chooses to preserve what’s left of his original identity, rejecting Apocalypse’s legacy.

Finally, we come to the main villain of the story, Stryfe. From his point of introduction, he is in nearly half the scenes in the story, with many of them serving as introspection as he rants to his silent henchman, Zero. The theme of legacy is woven into his entire character, and even his eventual grand plan revolves around it.

This is made the most clear once Stryfe truly introduces himself almost halfway into the event, declaring, “I am Stryfe! The crown prince of mutantkind. And you. The King and Queen of what is to come. “Father”-“Mother”-Welcome to the end of tomorrow!” In one moment, Stryfe has established his connection to Cyclops and Jean and placed the fault of coming events on their shoulders. In fact, Stryfe has placed the consequences of his own actions on their shoulders. This is essential to understanding the villain’s character.

Stryfe captures Cyclops and Jean Grey, imprisoning them and torturing them in psychological ways. He leaves them trapped in the dark, causing Cyclops to eventually lash out and realize that he’s hurt others who are imprisoned with him. He criticizes Cyclops’ inability to take responsibility for his mistakes. Stryfe insults the pair’s ability to nurture a child, to care for anyone other than themselves. In one particularly disturbing scene, he forcefully feeds Cyclops food, taunting that if even the villain knows how to nurture a child, Cyclops and Jean should, too.

Now, even ignoring what modern day readers may already know about Cable and Stryfe, it’s pretty clear that Stryfe views Cyclops and Jean as his parents and blames them for something that happened to him. And even in the 1992, Cyclops and Jean had sent their child, Nathan, to the future in order to save him after he was injected with the lethal techno-organic virus by Apocalypse. The implication in this mystery is that Stryfe is somehow Nathan all grown up, returned with a vengeance for what he views as being abandoned.

His taunts imply that he’s punishing them for abandoning him and either not knowing enough, or caring enough, to take care of him. He eventually traps the pair in a situation where they find a baby who looks like Nathan, and they only have the options of killing him (in order to kill all the villains coming after them) or abandoning him.

Of course, given the ridiculous situation, they choose to stay and fight to protect the child, but Stryfe seems genuinely confused by their actions. He had no doubt in his mind that they would hurt or abandon the child in order to save themselves. This is clearly because that’s what he felt was done to him: he’s the child, and he’s made himself believe that his parents must have been cruel. Who else would knowingly abandon him?

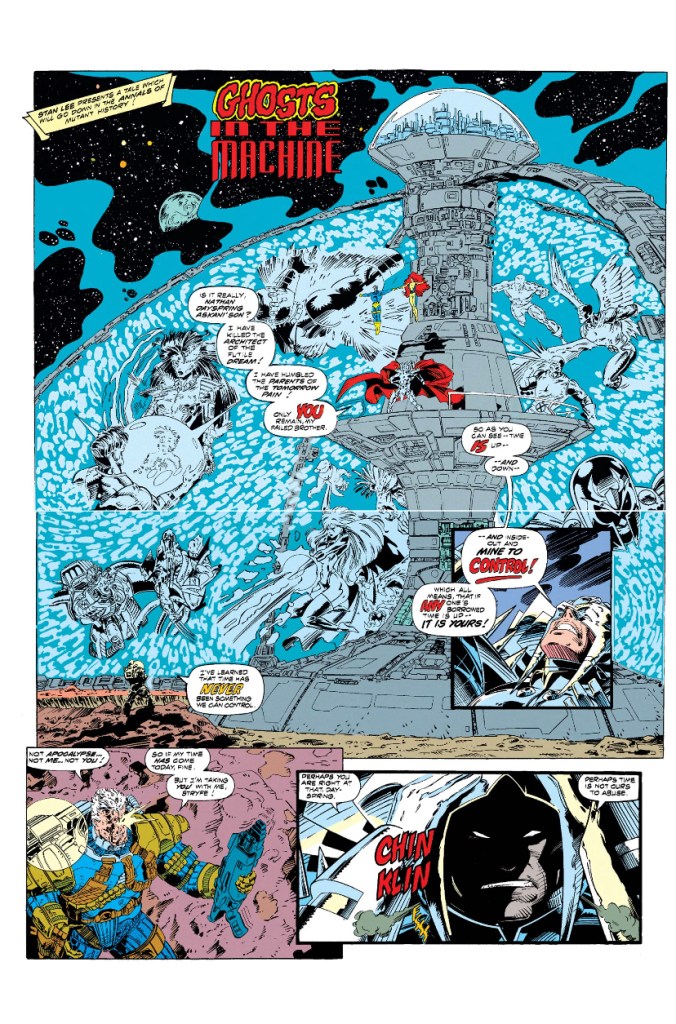

Another scene that illustrates Stryfe’s thoughts and abandonment complex is his ambush of Apocalypse. Stryfe taunts and overpowers the weakened villain, only barely allowing him to escape via a teleportation platform. His taunts speak volumes to his mindset, however.

“You owe me for everything that’s gone wrong with my life! You owe me a world for the wrongs you have foisted upon it!” Stryfe yells as he slams Apocalypse with telekinetic blasts. Here is even more evidence that Stryfe is likely Nathan, as Apocalypse’s virus was the reason he had to be sent to the future.

In truly tragic prose, Stryfe places the reasons for his abandonment upon Apocalypse’s shoulders: “How long has it been since you cried a babe’s tears of need? How long has it been since you longed for the gentle warmth of a mother’s touch? Do you want to know how long it has been for me? It has been forever! A forever solitude brought on by you, father of pain, son of the morning fire!”

Apocalypse gets a glimpse of Stryfe’s face, which is eerily similar to Cable’s, but he still never quite states if he knows what he’s being blamed for. It’s fitting, since Stryfe remains tragic when no one understands his woes or his motives. It’s also important to note that it’s eventually revealed that Cable and Stryfe are identical in appearance.

This clears up the fact that it was Stryfe who shot Professor X, but Cable still doesn’t know why they look identical. Fittingly, he doesn’t much care. When it’s implied that he may be a clone and Stryfe may be his original, he adamantly yells that he’s his own man. This brings us to the finale, and Stryfe’s grand, yet subtle master stroke.

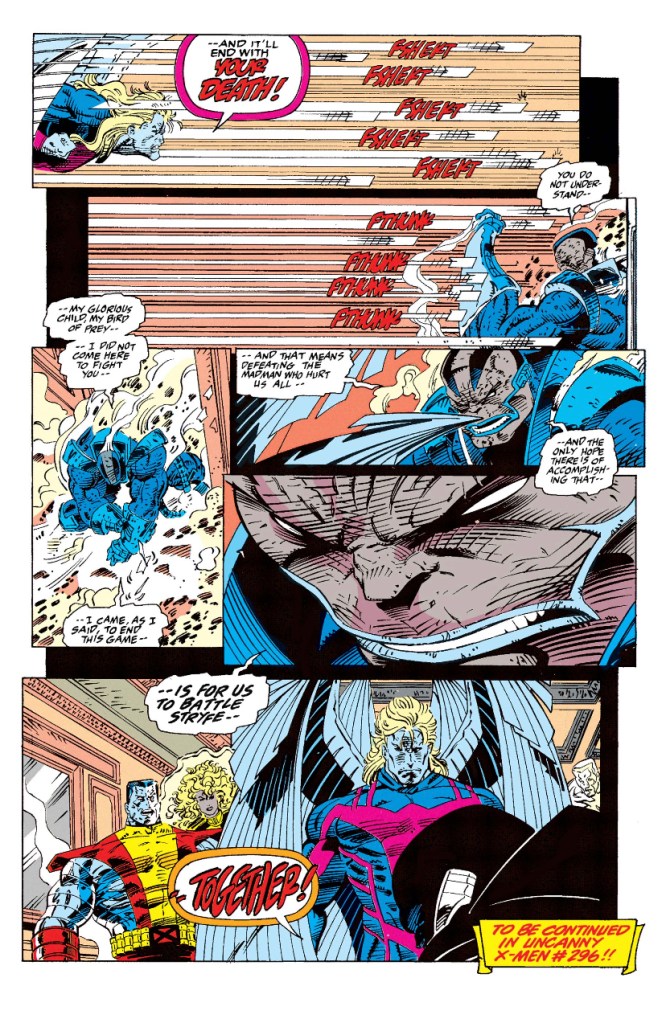

Bear with me at the context that you’re likely to find ridiculous: Stryfe has Cyclops and Jean trapped on the moon, attached to some giant device that’s functions are never revealed, although Stryfe’s taunts and the surrounding spectral images from their past imply that he wants to alter the timeline. The X-Men arrive to save them, but a shield is keeping everyone out except for those with the Summer genes: Cyclops’ brother, Havoc, and Cable himself. As Stryfe taunts Cable with not realizing why they made it through the barrier, he refers to him as “my failed brother”.

At this point, we have enough clues to link everything together: either Cable or Stryfe is the original Nathan Summers, somehow returned from the future. Who’s the original and who’s the clone? At this point, we don’t know. Although the fact that half of Cable’s body was ravaged by Apocalypse’s techno-organic virus and Stryfe’s is revealed to be unafflicted gives us a pretty good guess at who is the original.

Cable and Havoc fight against Stryfe to free Cyclops and Jean. Havoc’s plasma blasts burn Stryfe’s face, as Cyclops and Jean beg him to give up the fight so they can find a way to resolve his emotional problems and “stop this cycle of pain”. Here, we have what I view as the most compelling and tragic scene of the entire event.

“I want to believe you. I do. But how can I? Why am I suffering this way?” The pain on Stryfe’s burned face is beautifully illustrated, driving home just how much abandonment has destroyed him. Even in this vulnerable moment, he’s unable to accept their help. He wipes tears from his eyes before resolving that he’s still the victim, and that his actions are justified.

“I’m not the guilty one! You are! All of you are!! I leave you what you left me—A legacy of hatred! A legacy of decay! A loss of hope-A loss of life-A pox on all of mutantkind!” Stryfe unleashes destructive telekinetic energy as he cries out in rebellion of Cyclops, Jean, Apocalypse, Professor X and all mutants. Coming full circle from his introduction, he blames everyone before him for his lonely life that led him to hatred: that’s the legacy he believes he was left with, and so that’s what he has paid back to them.

“Look at me with pleading eyes! Ask me for help! Ask me to be your salvation! Ask me!” Stryfe is desperate to be needed, and one can assume that he wants Cyclops and Jean to ask him for help just so he can deny them. He was left in need of help, in need of nurturing, and essentially, in need of love. Stryfe never received it and vindictively seeks to show his parents how that feels.

The event ends with Cable sacrificing himself to stop Stryfe, both of them disappearing is a vacuum-like implosion that leaves no trace of them, except their pained cries of death: the titular executioner’s song. At the very end, Cyclops and Jean seem to realize that Cable was likely their son, Nathan, and vow never to forget his sacrifice.

It seems like a final, ironic jab at Stryfe that even in the end, Cyclops and Jean realize that Cable, not Stryfe, was their real son. However, while Stryfe’s vague plan of retribution failed, he orchestrated a back-up plan: in the final moments of the story, we learn that Stryfe manipulated Mister Sinister into unknowingly releasing the deadly Legacy Virus. This is the aforementioned “pox on all of mutantkind” that would go on to target and kill many mutants and humans in future X-Men stories.

It took me a surprisingly long time to realize this, but it should’ve been obvious given how significant the concept of legacy is in the story. Stryfe is a tragic villain, as he is indeed later revealed to be a clone of Cable who was raised by an abusive, future-version of Apocalypse. In the end, Stryfe’s “legacy of hatred” was literal, too: a malignant, deadly manifestation of a life without love. While X-Cutioner’s Song is admittedly crowded and confusing at times, it delivers thoughtful, powerful moments by truly focusing on the concept of legacy and displaying how it can manifest in inheritors, both positively and negatively.

(Uncanny X-Men (1963) #294 Cover Art-Penciler: Brandon Peterson, Inker: Terry Austin, Letterer: Chris Eliopoulos, Colorist: Mike Thomas)